Structure for the Unstructured. A Different Perspective on Clean Architecture for Domain-Centric Applications

The motivation behind writing this article is the desire to share my personal observations on running multiple Domain Driven projects in the last several years. There has been a lot of fuss lately on Twitter regarding the topic of Clean Architecture, so I decided that perhaps right now a good time to share what I believe in these days.

I have been pursuing a path to find a structure of the application that works for most teams and provides maximum ergonomy within the lifecycle of the project. I am also guilty of following the mainstream Clean Architecture with four main layers for several years blindly and I have seen the negative effects of the typical approach, which were hard to recover from.

The goal of the article is to provide an alternative structure based on Clean and Onion Architecture that has proven beneficial for the teams I have been part of. Sometimes to see clearly, we need to liberate ourselves from dogmas and “best practices” of the industry.

Promise of Clean Architecture

Clean Architecture is a software architecture approach that emphasizes the separation of concerns in a system and focuses on creating loosely coupled, independent components. You organize your codebase in four main layers: Domain, Application, Infrastructure and User Interface. The layers follow a set of strict rules, like Domain can’t rely on Application and User Interface layers.

The main intention is to focus on the Domain layer itself, which represents the real-world concepts, behaviors, structures and rules that the system models. From the Domain layer we thread up and maintain the clean separation of concerns. The idea itself is great and it’s definitely a step from any architecture that entangles all the concerns together (I’m looking at you the descendants of the MVC).

Unfortunately when the project and the domain scope grows, the layers do not live up to save us in the long run, as they do not provide powerful enough structure to keep us organized, nor they prevent us from entangling all concepts within the layer itself. We need a more principled approach that would guide us into creating a long lasting, ergonomic structure.

Focus on the Domain and the entanglement inside single layer

Several highly starred templates on Github for Clean Architecture reveal the initial structure as follows:

├───Domain

│ ├───Common

│ ├───Entities

│ ├───Enums

│ ├───Events

│ ├───Exceptions

│ └───ValueObjects

├───Application

├───Infrastructure

├───UserInterface

Having a clean separation of our Domain layer is a great treat, but do we really know what is going on exactly? Do we know what sort of project it is? Does it handle invoices, file management, scheduling? In order for us to know, we would have to traverse between folders inside the Domain project, glue the representation of the problem space in our head and then we are able to come to conclusions. The structure is definitely not domain revealing.

On top of that, what happens if our project has a set or problem spaces that we may want to keep separated? Would we pour all concepts together inside Entities, ValueObjects and more? Keeping a single layer of separation for all connected, semi-connected or disjoint problem spaces can lead up to the Domain Spaghetti itself. All concepts will be separated by a technical layer, which should provide some degree of separation, but what stops us from entanglement of all concepts like Shipments, Scheduling, Simulations, Audit Log, File Management and more together and dependent on each other?

Side note

Imaging a use case where you would separate your holiday files into logical layers as follows:

├───my-children-photos

└───my-photos

├───photos-in-the-woods

│ └───photos-during-the-day

│ 1.jpg

│

└───photos-on-the-beach

└───photos-during-the-day

1.jpg

There is definitely a logical separation for this use case, and the physical realm of the structure follows the logical realm that we created. Imagine tho trying to figure out which set of photos were taken and part of the given trip. It’s definitely not possible without a lot of labor. Sometimes I think of this example when discussing the logical -> physical discrepancy in the way we structure software projects.

Models arise

As the application scope grows, the multitude of models will definitely arise and maintaining healthy connections between different models can be a challenging task. The deeper we go, the more confusing the scope of the single model itself can become, as one model is deemed to have different meaning, depending on who is looking and interacting with it.

"Multiple models are in plan on any large project. Yet when code based on distinct models is combined, software becomes buggy, unreliable, and difficult to understand. Communication among team members becomes confused. It is often unclear in what context a model should not be applied."

> Eric Evans, Domain Driven Design - Tacking Complexity in the Heart of Software

Without providing a set of boundaries around our models, the structure of the project can lead to something as follows (Domain Spaghetti mentioned earier):

├───Entities

| ├───Deliveries

| | Delivery.cs

| | Tracking.cs

| | Attachment.cs

│ | Shipment.cs

│ | User.cs

│ | Order.cs

│ | Quote.cs

| | Invoice.cs

├───Repositories

| IShimentRepository.cs

| IUserRepository.cs

| IOrderRepository.cs

| IDeliveryRepository.cs

The structures similar to the listing above I have found throughout many years of developing software. They can also be found in most of the sample projects on Github. On a smaller scale it usually works fine, but as more and more models need to interact with each other in different contexts, the lack of separation in the scope of single logical boundary can lead to confusion in the long run.

The set of boundaries around models is known as Bounded Context separation. It defines the scope of the model and separates different areas of the domain into smaller parts, each with its own language, concepts, and rules. Bounded contexts help manage the complexity of the domain, ensuring the model accurately represents the business requirements and is cohesive and consistent. It is worth mentioning that having a set of boundaries is useful not only for business domains, but for any technical and functional domains as well.

In order to have a visible line that separates given set of models, we need a physical separation of those contexts. Physical separation can be a namespace, folder, package, depending on the language we are operating within.

Bounded Contexts itself may not be enought and inside one context we should still strive for a modular design that would separate sub problems around our core models.

Having a physical separation makes us more principled in the way we structure modules and communications between modules itself. The approach to structuring applications called Modular Monolith takes that premise and enforces the physical separations of business concerns. This is a great step towards more maintainable software.

The given example from open source project looks as follows:

├── Administration

│ ├── Application

│ ├── Domain

│ ├── Infrastructure

│ ├── IntegrationEvents

│ └── Tests

├── Meetings

│ ├── Application

│ ├── Domain

│ ├── Infrastructure

│ ├── IntegrationEvents

│ └── Tests

├── Payments

│ ├── Application

│ ├── Domain

│ ├── Infrastructure

│ ├── IntegrationEvents

│ └── Tests

└── UserAccess

├── Application

├── Domain

├── Infrastructure

├── IntegrationEvents

└── Tests

The structure itself is definitely more intent revealing. We can see clearly all modules of the application defined by its physical boundaries. Inside the module itself the approach still favors layered architecture, but in this example the scope of layers is closed, making it much easier to maintain the project in the long run.

It’s definitely a step in the right direction.

Dissecting Structure with Upstream/Downstream Connected Components

The idea of restructuring the applications came after inheriting the first Actor based system written in Akka.

Actors are isolated units of computation that communicate with each other through message passing, making it easier to write highly concurrent and fault-tolerant applications in a distributed environment.

The structure of actor systems follows a hierarchical design which consists of supervisors, “managers” and other nodes that follow through to the lowest leaf level. Unfortunately by design, nothing was stopping the development of creating an untangled web of communications that spawn in any sort of direction. The Actors could communicate upstream, downstream, in the same level, or to the other levels of totally different topological spaces.

Problems from this kind of communication (which spawns in any direction) can arise when changes made to one component have unintended consequences on other components, leading to errors, bugs, and unexpected behavior. Additionally, dependencies can make it difficult to modify or replace individual components without affecting the entire system, making it harder to evolve the software over time.

In order to figure out what sort of lifecycle and any subsequent invocations of dependent processes one particular message is responsible for, the whole graph of connections had to be recreated in the brain. Every day the process repeated itself, as our brains are not designed to store that kind of information well.

Having a single component of the application connected to any arbitrary number of components within the space itself has proven not to be too ergonomic.

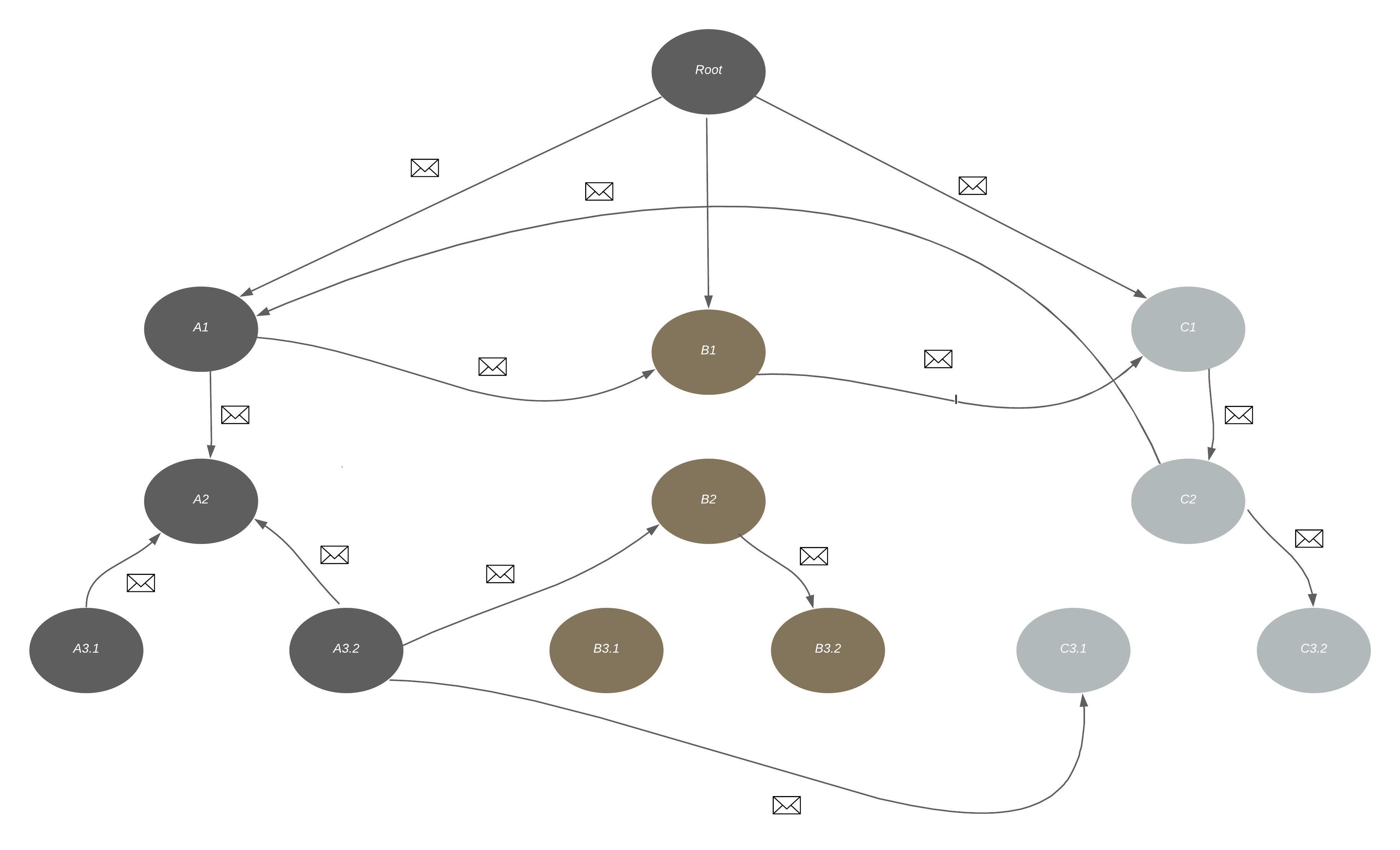

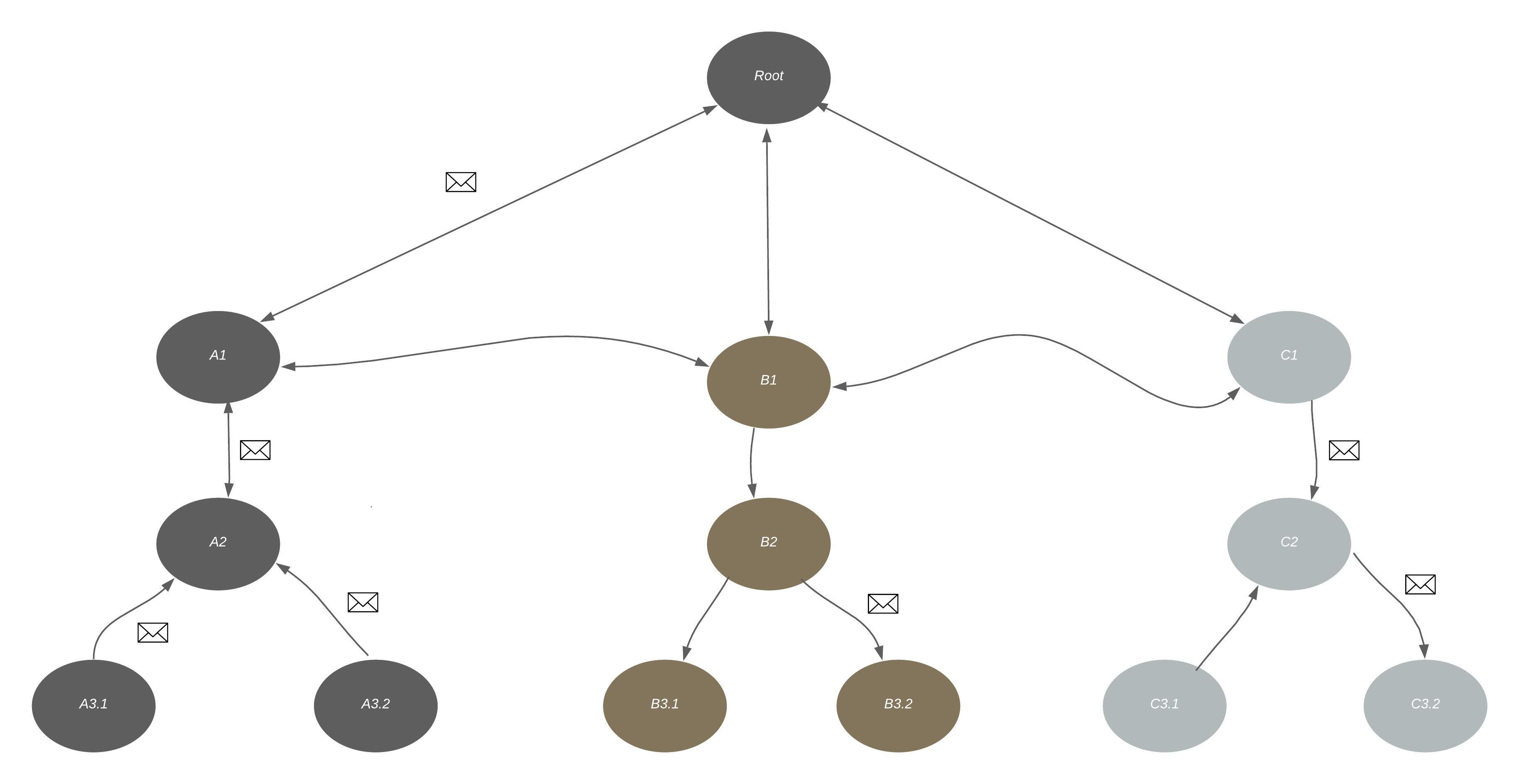

The idea to make it much more developer friendly, was to follow a set of OTP guidelines, while making sure the sub-spaces can communicate with each other only near the top level. This small change made a tremendous effect on the daily work with the application:

The sample images may not outline the great difference at first sight, but imagine more problems spaces and how the complexity of communications can grow. With some rules in place, the components could communicate mostly upstream and downstream up to the top level, and on the top level they could communicate sideways with other components inside the same hierachical space. It could sometimes mean that we are just forwarding messages upstream and to the side, but the benefit of that is that we could reason about certain process spaces independently of each other.

I took this idea and tried to re-model layered and per module structure, so we can follow the same set of heuristics. It would mean that in order for us to find all connected components for a single Domain concept, we would have to traverse in depth first approach and find all the connections downstream. That would eliminate a whole lot of search space to find the connections between our logical model and what forms the functionality as a whole.

With a standard four layered approach it is hard to take a given model and find all its connections, as we have a parallel layer separation for domain space, application, infrastructure and user interface concerns. The byproduct of that is that we always need to traverse upstream and to the sides to find all components that may be related to our model itself.

Note that the shared libraries designed to be used by different modules can be referenced in multiple places inside our tree structure with no problem. Thats what they are designed for in the first place.

Evolving Structure

Whenever we structure the domain applications, data engineering applications, or libraries, the approach of putting our main models or structures in the root, will make the application intent revealing for the reader and we will be able to indentify the path in which we may find the connected components that forms the solution space as a whole.

We can illustrate the structure evolution on the toy example of a domain for shipping arbitrary objects.

│ IShipments.cs

│ Shipment.cs

│ ShipmentId.cs

│ ShipmentService.cs

│ ShipmentStop.cs

│

└───_Infrastructure

DatabaseShipments.cs

InMemoryShipments.cs

If we fight the urge to put everything in a folder upfront via technological separation like Service, Entity, Repository, we would end up with most of the files at the root level. Everything related to the main concept of Shipment would be as close to the model as needed.

I call this concept Domain Proximity Meter. It indicates how far we need to reach in order to form a whole problem space from its main domain model. There could be queries for the model, repositories, services, implementations, user interface concerns that are associated with one logical component. The further we need to search for it’s connected parts, the less ergonomic the whole space formulation becomes.

Now let’s say we introduce a sub problem space of reporting delays. Our structure could evolve as follows:

│ IShipments.cs

│ Shipment.cs

│ ShipmentId.cs

│ ShipmentService.cs

│ ShipmentStop.cs

│

├───Delays

│ │ DelayReport.cs

│ │ DelayReson.cs

│ │ DelayService.cs

│ │ IDelayReports.cs

│ │

│ └───_Infrastructure

│ DatabaseDelayReports.cs

│ InMemoryDelayReports.cs

│

└───_Infrastructure

DatabaseShipments.cs

InMemoryShipments.cs

We have separated the sub problem space of delay reports into its own folder. Everything related to delay reports can be found inside the Delays folder itself. On top of that, the DelayReport can reference the ShipmentId from the root level, preserving our rules about component dependencies.

If more and more problem spaces connected to our main concept evolves, we still keep our rules and follow the guidelines. Let’s say we are now modeling the state and transitions of

all activities that can happen from the moment the shipment delivery is started, to the moment the shipment is delivered.

│ IShipments.cs

│ Shipment.cs

│ ShipmentId.cs

│ ShipmentService.cs

│ ShipmentStop.cs

│

├───Delays

│ │ DelayReport.cs

│ │ DelayReson.cs

│ │ DelayService.cs

│ │ IDelayReports.cs

│ │

│ └───_Infrastructure

│ DatabaseDelayReports.cs

│ InMemoryDelayReports.cs

│

├───Deliveries

│ │ Delivery.cs

│ │ DeliveryActivity.cs

│ │ DeliveryHistory.cs

│ │ DeliveryService.cs

│ │ IDeliveries.cs

│ │

│ └───_Infrastructure

│ DocumentDbDatabaseDeliveries.cs

│ InMemoryDeliveries.cs

│

└───_Infrastructure

DatabaseShipments.cs

InMemoryShipments.cs

Not much has changed, as we have just separated the problem into its own substructure. This kind of approach enforces modular design of the applications and makes sure we make conscious decisions as our application evolves. All related components are close to each other, making it easy to digest.

Evolving Structure Based Around CQRS

If we are fans of Commands, Queries and strict layers, nothing is stopping us from using them with the approach described above. We would just make sure the folder or namespace explicitly separates the domain from the other concerns. There might be some different rules if we want to maintain the structure cross layers, as definitely some paralell connections will arise, but we should strive to minimze them.

If we like the CQRS approach, the sample structure could evolve into something as follows:

│ IShipments.cs

│ Shipment.cs

│ ShipmentId.cs

│ ShipmentStop.cs

│

├───Delays

│ DelayReport.cs

│ DelayReson.cs

│ IDelayReports.cs

│

├───Deliveries

│ Delivery.cs

│ DeliveryActivity.cs

│ DeliveryHistory.cs

│ IDeliveries.cs

│

└───_CQRS

│ TestData.cs

│

├───Commands

│ │ AddNewShipment.cs

│ │ CancelShipment.cs

│ │

│ ├───Delays

│ │ ReportDelay.cs

│ │

│ └───Deliveries

│ PerformActivity.cs

│ StartDelivery.cs

│

├───Queries

│ │ IShipmentQueries.cs

│ │

│ ├───Delays

│ │ IDelayQueries.cs

│ │

│ └───Deliveries

│ IDeliveryQueries.cs

│

└───_Infrastructure

│ DatabaseShipments.cs

│ InMemoryShipments.cs

│

├───Delays

│ DatabaseDelayReports.cs

│ InMemoryDelayReports.cs

│

└───Deliveries

DocumentDbDatabaseDeliveries.cs

InMemoryDeliveries.cs

In the approach listed above, we would keep our domain close to the root and then thread down into application and infrastructure layers. We separate out commands and queries and inside each layer, we replicate the structure to have a symmetry with our domain space. I find this to be a very ergonomic structure.

Eliminate Dependencies Between Namespaces

Another great rule is to strive to eliminate dependencies between namespaces. In normal package design, the package manager would detect cycles and prevent us from doing such things, but unfortunately the free folder structure will allow us to create cycles. We could use static analysis tools to detect them early on. For the example above it would mean that the general CQRS rule of commands not depending on queries enforced by design.

The structure still follows upstream/downstream design, but the introduction of explicit layers (denoted by underscore), will still force us to make some parallel connections. As mentioned above, they will happen, but we should strive to minimize them.

Summary

The ideas formulated in the article may not look like anything spectacular, but as a manager responsible for deliveries or products, I have found them to be actually profound on the microscoping level of the software architecture. Developers didn’t need to think about upfront separation. They could just form their models, write the contracts for any potential side effectful operations on the models and formulate the solution as a whole. The rules worked well for larger domains, where just folders provided additional structure for a sub problem space. The ability to find all related components quickly and closely made a tremendous impact on the daily deliveries of new features and the low level of regressions.

Here are a few rules to make sure we summarize the content of the article:

- Focus on the main model first when working on a problem

- Thread downstream from the model and try to keep connected components close as possible

- Avoid cycles in namespaces (huge)

- If using layered approach, consider physical separation indicating layer switch (like denoted by underscore or similar)

- If using layered approach,follow the symmetry cross layers that would replicate the structure of the domain layer itself.

I hope some of the readers will reconsider the general structure of the applications and find it useful. We just scratched the surface and there are many other things to consider when structuring the application (like cross context communications), but hopefully the ideas from the article could be a good starting point. It’s definitely important to keep the conversation open and always iterate on top of what we’ve already know.